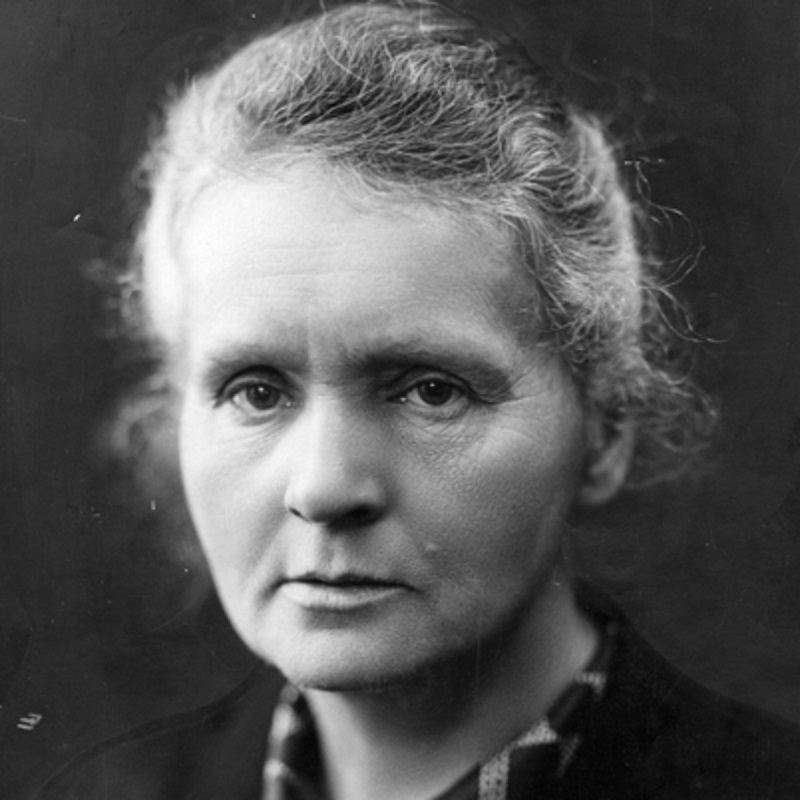

Marie Curie is a hero to us. She was born in 1867 in Warsaw, Poland and was part of a group of scientists whose work ushered in the Atomic Age we live in now. She is called the First Lady of Science and when she was 36, she became the first woman to receive the prestigious Nobel Prize for her research into radioactivity. For her work isolating the element Radium, she later became the first and, to this day, only individual to win the Nobel Prize in two different sciences. Her life and work provide a remarkable example the advantages and dangers inherent in scientific progress as well as the power of determination. You know that song Radioactive by Imagine Dragons? Well, it’s the first thing that pops up when you search the word ‘Radioactive’ online, but you can thank Marie Curie for inventing the word!

Both of the future laureate’s parents were teachers, instilling in Marie, the youngest of five, a desire to learn and discover. However, Marie faced a number of significant obstacles throughout her life. At the time of her birth, the territory once controlled by a commonwealth of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had been conquered by and divided between the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy, the Kingdom of Prussia and the Russian Empire. She lived in an area known as the Russian Partition, where imperial rule was harsh and oppressive: Polish language and culture was outlawed and girls were forbidden from attending higher education.

During Marie’s childhood, her father lost his job due to his political stance against Russian rule and her oldest sister and mother died (the former from typhus and the latter from tuberculosis). Marie kept her passion for science alive, however: she worked to support her older sister attending school in France in exchange for that sister’s assistance after her graduation.

In 1891, Marie made it to a prestigious university in Paris known as the Sorbonne. Three years later, she received her degree in physics and also met Pierre Curie. The two were married in 1895 and began what would become one of the greatest collaborations in the history of science.

Around that time, there were major advances being made in physics and chemistry regarding electricity, magnetism and their effects on different materials. One common experiment was to put an electric current through a material in a vacuum tube and observe the rays of light which the material emitted. In 1895, the same year as Marie and Pierre’s marriage, a German/Dutch physicist named Wilhelm Röntgen discovered that certain elements, when subjected to an electric current, would emit rays that even pass through an opaque barrier, such as cardboard. He entitled these rays x-rays and eventually managed to produce an image of the skeleton of his wife’s hand.

The next year, French scientist Henri Becquerel, working in Paris, observed that the element uranium would spontaneously, i.e. without an electric input, produce rays similar in their penetrative power to x-rays. Marie was interested in the nature and possible applications of these rays and began research into uranium. She identified a higher degree of radiation in pitchblende, a uranium ore, and accordingly realized that there must exist within the ore additional and more active elements: one of these turned out to be thorium, discovered by Marie as the second radioactive element. In 1898, Marie and Pierre working together isolated a further radioactive element from the uranium ore, which they named polonium after Marie’s native country. The second element the Curie’s discovered they named radium, after the Latin word for “ray,” as in a ray of light.

Marie faced another great tragedy in 1906, when her husband was struck and killed by a carriage in heavy rain. Following this, Marie had to maintain her credibility as a scientist against claims that she was merely riding the coattails of her husband. Her fight against the male-dominated establishment earned her a professorship at the University of Paris. In this new position, she isolated radium in 1910, earning her a second Nobel Prize, this time unshared (the previous award was shared between Marie, Pierre and Becquerel).

The Curies’ work proved immensely impactful on science and medicine. For one, their research helped establish the divisibility of the elemental atom. The theory of the time held that fundamental elements, such as hydrogen, oxygen, iron and radium, were composed of indivisible particles known as atoms. When Marie recognized radioactivity emitting from uranium without any external stimulation, she concluded that there must be some phenomenon within the atom responsible for the emission. In the following decades, scientists such as Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr developed models of the atom, in which the negatively-charged electrons orbit around a positively-charged nucleus, which is a core made of protons and neutrons. Electromagnetic radiation is emitted as a result of changes to the atomic structure: an electric current can change an electron’s energy level, causing the emission of an x-ray photon, or particle of light; an unstable nucleus can break apart into different elements, resulting in the emission of higher-energy photons.

Cancerous cells, Marie observed, exposed to radium die more quickly than healthy cells. Radiation treatment holds a great deal of promise for individuals suffering from cancer. However, the work of the 20th century atomic scientists led to the development of the most destructive weapon ever created: the atomic bomb. In 1942, the United States began the Manhattan Project, a secret operation to develop a weapon based on the principle of nuclear fission: i.e. atoms release immense amounts of energy when they split. The first test of such a weapon was conducted on July 16th 1945 – the first two models were used in warfare against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima (August 6th) and Nagasaki (August 9th), resulting in perhaps 200,000 civilian deaths.

Curie’s death came on July 4th, 1934 due to aplastic anemia. The disease, in which blood cells inside the bone marrow become damaged, was caused by her prolonged exposure to radioactive elements, whose danger was not known in full. Her legacy lived on through her daughter Irène, who won a Nobel Prize herself in 1935 for her and her husband’s work with artificial radiation. Indeed, that legacy continues to this day as scientists, male and female, draw inspiration from the passion of Marie and Pierre for discoveries that have the power to change the world.

Ever thought about giving monthly to a truly heroic cause?

The Thanda Superheroes are a group of monthly donors who are fighting food insecurity, poor education, and unemployment – creating real and lasting change in rural South Africa. With these powers, they are building a world where everyone can be a hero in their own communities.

Join the fight today at www.thanda.org/